After Ancient Sunlight

Materials for a Post-Petroleum World 2018

Abstract

After Ancient Sunlight investigates how present-tense photosynthesis—rather than fossilized photosynthetically captured carbon—can serve as a basis for contemporary material culture. Through a Research through Design approach, I developed a translucent, carbon-negative bioplastic derived from marine macroalgae and fabricated a functional raincoat from this material. The work reframes plastics as a decentralized carbon capture and storage medium and demonstrates the cultural and technical viability of post-petroleum materials. As a proof-of-concept, the project links the chemistry of materials to the psychology of climate action, illustrating how familiar, desirable artifacts can make planetary carbon flows tangible and emotionally legible. The resulting prototype has informed subsequent patent filings, interdisciplinary collaborations, and institutional research directions toward biogenic materials for climate-positive design.

“Fashion’s application of natural carbon sequestration has been pioneered by Charlotte McCurdy, who in 2018 created ‘After Ancient Sunlight,’ a carbon-negative raincoat made of marine macroalgae biopolymers.”

Andrew Bolton Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion The Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

biogenic materials; carbon-negative design; marine macro-algae; bioplastics; material decarbonization; Research through Design; double-diamond process; ancient sunlight; present-tense carbon; charismatic object; climate communication; design for planetary systems; renewable manufacturing; post-petroleum economy; cultural prototyping.

Introduction and Context

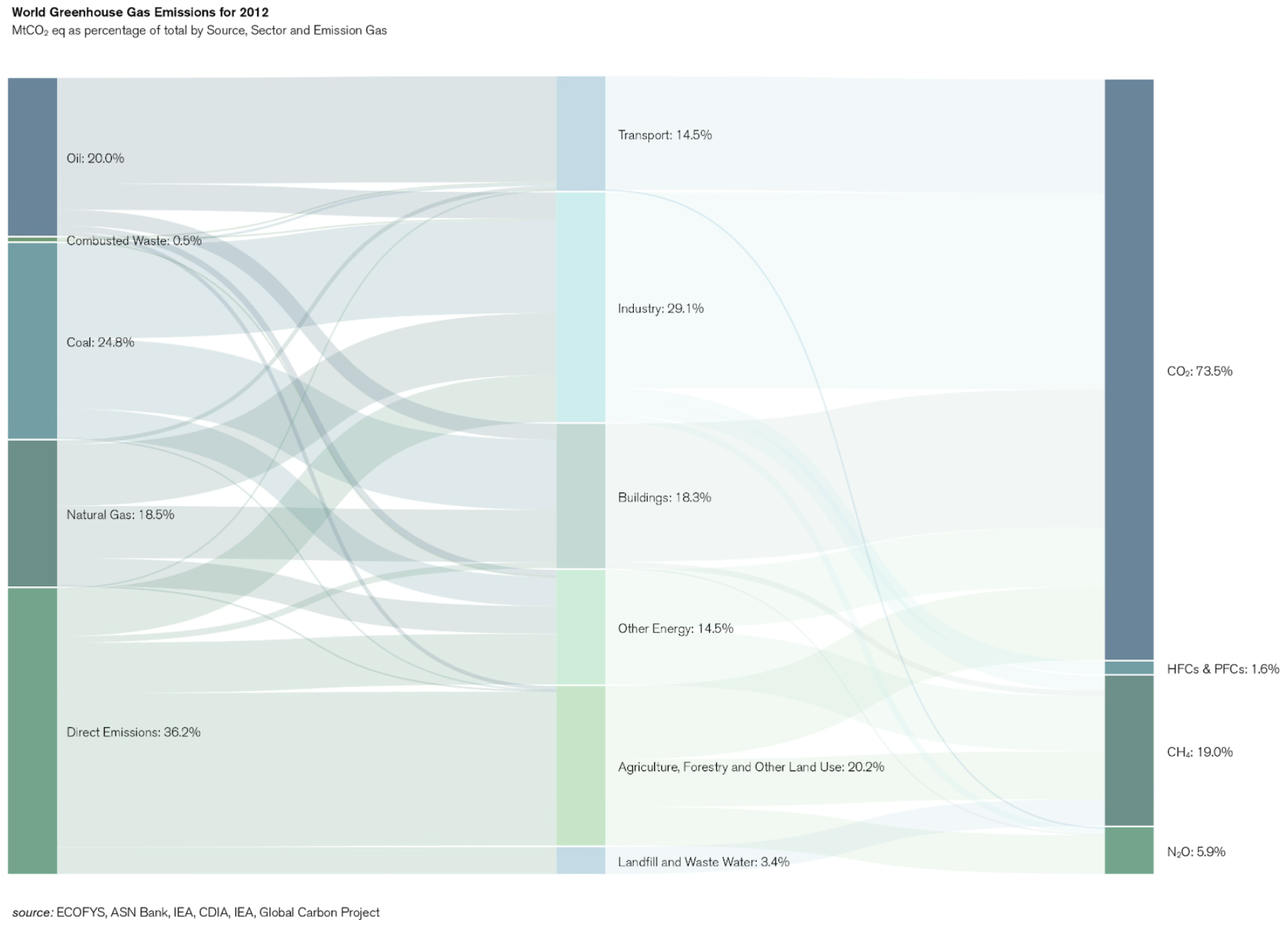

Modern material culture is built on fossil carbon. Every polymer, pigment, and solvent derived from petroleum, natural gas, coal, or limestone links daily life to ancient photosynthesis—the compressed remnants of organisms that captured sunlight hundreds of millions of years ago. These “ancient sunlight” materials have enabled extraordinary technological progress but now anchor a global emissions problem that extends far beyond energy production. Industrial processes that convert oil into chemicals, limestone into cement, and iron ore into steel account for roughly one-fifth of total anthropogenic CO₂ emissions. Decarbonizing these material flows is therefore as urgent as decarbonizing electricity or transport, yet it has received comparatively little investment, public imagination or design attention.

The project posits that a viable post-petroleum society will depend not only on technical substitution but also on cultural legibility. Renewable materials must not only perform; they must make sense within the habits, aesthetics, and economies of everyday life. To explore this, I adopted a Research through Design methodology in which iterative material experiments serve as both scientific inquiry and public proposition. Working with marine macro-algae, I developed a translucent bioplastic capable of forming a water-resistant film suitable for garment fabrication. The resulting artifact—a raincoat—acts as both prototype and argument: evidence that biogenic carbon can meet human needs while drawing down atmospheric CO₂.

By coupling material engineering with narrative form, After Ancient Sunlight operates across technical and perceptual domains. It situates the laboratory bench alongside the museum gallery and the carbon cycle diagram alongside the fashion image. In doing so, it reframes decarbonization as a design problem—one that requires the invention of new materials and new meanings simultaneously.

Background & Literature

After Ancient Sunlight began as a response to that imaginative gap. Rather than treating materials as neutral substrates, the project treats them as active sites of climate agency. It asks how design might make the planetary carbon cycle tangible, desirable, and actionable through the creation of new substances. The phrase “ancient sunlight” reframes petroleum, coal, and limestone not simply as resources but as geological archives of past photosynthesis—reminding us that the essential chemistry of carbon fixation and polymerization remains available to us in the present tense.

Efforts to decarbonize material production have historically focused on efficiency and substitution rather than transformation. The prevailing industrial paradigm, what Natalie Jeremijenko terms the “logic of reduction and displacement,” has sought to minimize harm rather than redesign systems altogether. William McDonough and Michael Braungart’s Cradle to Cradle (2002) articulated the limits of this paradigm, calling for circular material metabolisms in which waste becomes feedstock. Yet even within such frameworks, carbon is still treated primarily as a pollutant to be reduced or contained, not as a design material to be centered or aestheticized.

In parallel, speculative and critical design traditions—from Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby’s Speculative Everything to Neri Oxman’s Material Ecology—have demonstrated how artifacts can act as vehicles for research questions.

In another related tradition, empowered by Rittel and Webber’s “Wicked Problem” framework, Frayling’s category of Research through Design (RtD) has emerged as a formal methodology applied to under-constrained problem spaces where the act of prototyping itself produces insight.

Fig. TK | Henry Ford giving a demonstration where he strikes the body of his plant-polymer car with a sledgehammer to demonstrate its strength. photo: Bettmann / Getty Images

In sustainability research, RtD has been used to explore behavioral change, product longevity, and speculative futures, but rarely to investigate industrial chemistry or carbon accounting. The After Ancient Sunlight project extends RtD into the domain of materials science, using design as a research instrument to link the cultural, chemical, and climatic dimensions of matter.

Design scholarship also emphasizes the role of artifacts in shaping collective imaginaries. Donella Meadows identifies “paradigm shift” as the highest leverage point in a system, and design—through visibility and affect—can accelerate such shifts. After Ancient Sunlight contributes to this discourse by making the invisible carbon cycle perceptible, situating global-scale decarbonization within personal experience and aesthetics of everyday life.

By synthesizing insights from materials science, environmental systems theory, and design research, this project frames carbon not as waste but as a medium. It builds on emerging discourse around “design for the bioeconomy,” while challenging its tendency toward eco-branding and incremental substitution. Instead, it advances a model of design as epistemic practice: producing knowledge about how new materials can function simultaneously as climate technology, industrial prototype, and cultural communication

Historically, the dominance of petroleum-based materials is as much sociotechnical as it is chemical. Before World War II, plant-based polymers such as cellophane, rayon, and soy plastics were commercially viable. Henry Ford’s 1941 “soybean car,” made with agricultural polymers, exemplified this trajectory. Wartime resource allocation, however, directed research funding and infrastructure toward petrochemistry, institutionalizing an “accident of history” that made fossil carbon the default molecular building block of modernity. Synthetic polymers now account for over 400 million metric tons of annual production and more than 20% of projected oil consumption by 2050. Currently, 99% of pharmaceutical feedstocks and reagents are derived from petrochemicals, and the material products of hydrocarbons are subsidized co-products of fuels for sold for combustion.

Contemporary biomaterials research largely targets biodegradability, emphasizing end-of-life management over climate impact. Commercially available biodegradable plastics like PLA materials often rely on terrestrial feedstocks connected to carbon-intensive food systems. Marine algae, by contrast, offer a non-terrestrial, high-yield source of photosynthetic carbon, converting solar energy to biomass. Marine algae require no fresh water input and have the potential to expand total photosynthesis (net primary productivity) rather than substitute it like terrestrial biogenic feedstocks. After Ancient Sunlight leverages this biological potential not for energy but for materials—treating algae as a molecular manufacturing platform for carbon capture and storage in durable form.

Methods / Design Process

Discovery and Framing

This project was developed through an iterative design process modeled on the Double Diamond framework (Bánáthy, 1996), alternating between divergent and convergent, generative and evaluative phases. Rather than beginning with a fixed hypothesis, the work sought to discover and define its research question through cycles of making, testing, and reflection. The process unfolded as several layers of design work pursued in parallel—secondary research, expert interviews, hands-on material experimentation, and the creation and deployment of design probes as tools for eliciting reflection and feedback.

Initial inquiry began with broad secondary research into the historical entanglement between material culture and fossil carbon—from the chemistry of polymerization to the geopolitics of oil extraction. Interviews with marine carbon cycle experts, materials scientists, designers, and sustainability researchers helped clarify both technical constraints and cultural assumptions about “natural” versus “synthetic” materials.

Material Focus and Design Refinement

Generative Exploration

Early divergent explorations tested multiple media and scales of engagement, ranging from animation and projection mapping to 3D printing, solar data visualization, bookbinding, bronze casting, and bioplastic formulation. Each experiment was treated as a design probe to explore how different forms might provoke conversation about living in a post-petroleum society. These prototypes served as communicative devices—ways of eliciting “real listening” and bypassing cognitive fatigue around climate discourse.

During this period, the conceptual and language tool of “ancient sunlight” emerged: a reframing of fossil fuels, cement, and things made of them as materials made from molecules that store the energy of the sun, captured by long-dead photosynthesis. This construct provided a linguistic and conceptual pivot, allowing people to connect industrial materials back to the biosphere and to imagine “present-tense” alternatives. The paradoxical idea of an ancient ephemerality—a durable civilization built on extinct light—became a generative metaphor that unlocked new conversations and design directions.

What would it feel like to get back into a present-tense relationship with the sun?

Structural biopolymers extracted from several species of macroalgae were plasticized using glycerin and cross-linked through controlled dehydration. The formulation was refined across more than 40 series trials to achieve film-forming properties comparable to polyvinyl chloride (PVC). A parallel set of experiments went towards developing a waterproofing wax that was both petrochemical-free and vegan (which did not exist commercially), matrixing combinations of plant waxes and oils.

Results guided compositional optimization until the film exhibited sufficiently high surface contact angle, strength, flexibility, and clarity. The final polymer was cast into sheets, trimmed, and sewn together. Garment patterning followed a conventional raincoat silhouette to emphasize usability and emotional familiarity rather than novelty. This choice was deliberate: by embedding the material in a recognizable typology, the prototype invites users to imagine direct substitution for petroleum-based textiles without behavioral change.

Results, Impact, and Dissemination

The project produced a marine-algae-derived polymer film with sufficient transparency, flexibility and barrier performance to be crafted into a functional raincoat. This proof-of-concept demonstrates a viable pathway toward a carbon-negative materials system—one in which the carbon fixed by algae during growth can be durably embodied in consumer products when coupled with fully electrified renewable-energy processing. While a full life-cycle assessment has not been completed, the envisioned emissions pathway includes substitution of fossil-plastics, expansion of biomass carbon storage via aquaculture, durable carbon storage in product use, and at worst carbon-neutral end-of-life (or potential consumer-driven landfill sequestration). This dimension of the work led to utility patent US20220204653A1 “Carbon-Negative Bioplastic.”

The work’s diffusion into major exhibitions, media channels, and industry collaborations amplifies its cultural impact and positions it as an early exemplar of carbon-negative materials in the public domain, including: (1) being exhibited at Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum (Nature: Design Triennial, 2019) and other museums thematically spanning science, fashion, technology, and history; (2) covered by major news outlets including The Guardian, Fast Company, The New York Times, CNN, Vogue, Dezeen; and (3) reaching public television audiences through featured like that in the PBS series “Climate Artists” (Oct 2019).

By 2024, the project has reached an estimated > 8 million combined museum visitors, media readers/viewers, and industry stakeholders. (Estimate based on cumulative institutional, media, and industry engagements.)

FIGURE: Exhibition view of “After Ancient Sunlight” in the Cooper Hewitt Triennial 2019, as photographed by the New York Times

Discussion and Conclusion

After Ancient Sunlight demonstrates that the material transition required for climate stability cannot be achieved through substitution alone, decarbonization must also operate at the level of imagination to reconfigure how people understand and value materials. The project’s contribution therefore, lies not only in the invention of a new biogenic polymer but in establishing design as a methodology for systems translation: converting planetary-scale science into culturally intelligible forms.

The process shows that design can serve as an integrative mode of engineering inquiry—one that unites technical development, communication, and human behavior in a single research frame. The “ancient sunlight” construct operates simultaneously as an analytical model, a narrative device, and a design brief, allowing collaborators across science, policy, and art to align around a shared metaphor. This is not ancillary to scientific progress but essential to the social adoption of climate technologies.

The success of the project across museums, media, and communities suggests that public appetite exists for positive, materially grounded visions of decarbonization. Such artifacts operate as early “cultural prototypes” for a post-petroleum society—proofs not only of concept but of desirability. The diffusion of After Ancient Sunlight indicates that aesthetic and affective dimensions of sustainability research can materially influence industrial and policy discourse, translating climate goals into public imagination.

Ultimately, After Ancient Sunlight advances the argument that the decarbonization of materials is not merely an engineering optimization problem but a design challenge of world-building. The project demonstrates how design can expand the scope of engineering research to include cultural viability and human meaning—key variables in whether sustainable technologies actually succeed and scale. In reframing carbon as a medium of creativity rather than constraint, it points toward a regenerative industrial paradigm powered by present-tense sunlight.